|

|

Is it Time for RFID? Wal-Mart’s Lead Signals Widespread Adoption

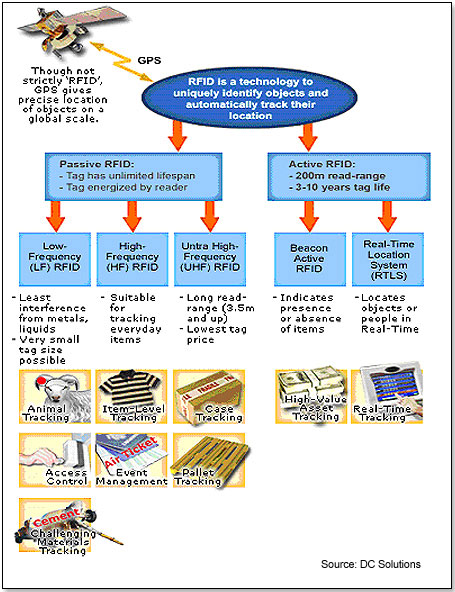

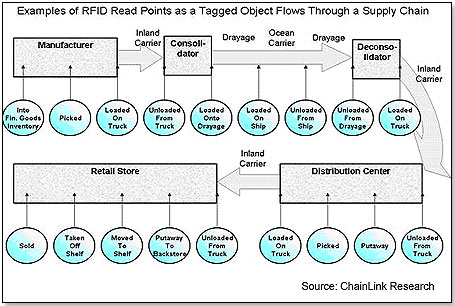

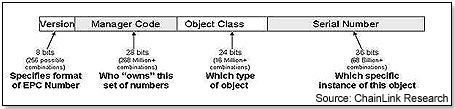

WAL-MART EMBRACES NEW TECH  In June 2003, Wal-Mart began testing RFID with eight manufacturers and one distribution center (DC), utilizing case- and pallet-level RFID tags. The system went live in January 2005 at the Dallas, Texas, DC. Now, five DCs, about 600 suppliers and approximately 1,000 stores are included in the RFID chain. Also, all Sam’s stores in the Dallas area are RFID-capable. In June 2003, Wal-Mart began testing RFID with eight manufacturers and one distribution center (DC), utilizing case- and pallet-level RFID tags. The system went live in January 2005 at the Dallas, Texas, DC. Now, five DCs, about 600 suppliers and approximately 1,000 stores are included in the RFID chain. Also, all Sam’s stores in the Dallas area are RFID-capable.The Sam’s DeSoto facility is the first Sam’s Club DC in the country where suppliers will be required to tag every case on a pallet (Oct. 31, 2008) and every item that makes it on to store shelves (Oct. 31, 2009). Sam’s will add another four DCs by October and the remaining 17 DCs by January 2009. Wal-Mart recently notified suppliers of its Sam's Club warehouse stores in Texas that it will charge a $2 service fee for pallets not tagged with RFID after January 2008, which makes selling Sam’s prohibitive once tagging drops to the unit level. Wal-Mart has not yet issued a similar timetable, but likely will sometime this year, including all 3000 stores for full implementation by 2010. TESTING PUSHES ADOPTION Staples, Target, Costco, Dillards, Best Buy, Levi Strauss, Albertsons and the U.S. Department of Defense are testing RFID and, in my opinion, will eventually force manufacturers and other retailers to adopt the technology to remain competitive. The main reason Wal-Mart is committed to complete RFID implementation is inventory control. A 2003 study co-published by professors Daniel Corsten and Thomas Gruen, respectively of London Business School and the University of Colorado, estimates that inventory shortages on the retail level reduce sales on average by 3 to 4 percent. Retail theft accounts for about 1.5 percent of retail sales. For Wal-Mart, these respective causes add up to $12 billion and $4.5 billion in sales lost. Given these numbers, and the many other benefits attending RFID, the technology is not going away. The only question is when it will affect mainstream manufacturers who supply Wal-Mart or other mass merchandisers. WHAT IT CAN DO While RFID can serve various purposes in a number of industries, here are some uses by which it may impact retailers and manufacturers: • Retail Inventory Control: product inventory, theft detection, point-of-sale verification • Manufacturing: track a product’s progress through the manufacturing cycle and tie an individual product to its current location; track when it was manufactured, whether it was received and where it is located • Logistics & Supply Chain: moving goods through loading docks; managing terabytes of data as information about goods on hand is collected in real-time • Container/Pallet Tracking • ID Badges and Access Control • Fleet Maintenance HOW IT WORKS In a typical RFID system, individual objects (pallets, cases, boxes, packages) are equipped with an inexpensive tag that contains a digital memory chip. This chip carries product-related data such as quantity, price, color, purchase date and manufacturing date. The tag has its own electronic code that can be read by an interrogator, which is an antenna containing a transceiver and decoder. This interrogator can, from anywhere in the world, send a signal to the chip and read the information contained in it, then pass the information on to its host computer. The tag is also activated if it passes through an electromagnetic zone that detects and reads the chip and then sends the data to the computer. There are two types of RFID tags: active and passive. The active tag has its own power source and can be used to send instructions to other receptors (e.g. give a machine instructions during the manufacturing cycle, and the machine will report the outcome to the tag). The passive one can only be read or added to. This is what the different RFID tags do:  We are in the context of this review solely concerned with Ultra High-Frequency [UHF] RFID chips. Once installed, they are tracked as part of a packaging unit through all stages of the supply chain.  The data typically contained in a passive UHF tag consist of four components:  1) Version: tells interrogator what format of RFID tag is being used 2) Manager Code: identifies the company (typically the manufacturer) that applied the code; one exception is when a third-party [e.g. Sam’s in Texas] applies the tag on behalf of the manufacturer 3) Object Class: tells what type of object has been tagged — for example, a pallet containing 6,000 units of six-packs of 12-oz. cans of Classic Coca Cola, with special packaging for Christmas 2008, designed for the Canadian market 4) Serial Number: differentiates one tagged object from the next coming off the production line, even though they may be identical (e.g. another pallet of six-packs of Classic Coca Cola) TRACKING THE COST Adoption of RFID is not immediate and widespread due to cost. While each case and manufacturer are different, this cost number is being quoted universally for second-tier manufacturers with sales between $50 and $100 million: one-time cost around $100,000, and timeframe for implementation between 10 and 12 months. The $100K figure breaks down as follows: hardware, $20K; middleware [software], $30K and external consulting and other services, $50K. While most manufacturers would want to enlist help from a service bureau to ensure smooth implementation — hence the $50K price tag above — they are well advised to ensure that the final choice is a good one, since many consultants falsely claim to be “state-of-the-art.” As for ongoing costs, passive UHF RFID tags run about $.30 per piece, and an EPC Global membership is $10K for a manufacturer with sales between $50 million and $100 million. Any company that goes down this path is well advised to get their best and brightest involved, led by one very senior executive whose main priority is RFID implementation.  Writer's Bio: Lutz Muller is a Swiss who has lived on five continents. In the United States, he was the CEO for four manufacturing companies, including two in the toy industry. Since 2002, he has provided competitive intelligence on the toy and video game market to manufacturers and financial institutions coast-to-coast. He gets his information from his retailer panel, from big-box buyers and his many friends in the industry. If anything happens, he is usually the first to know. Read more on his website at www.klosterstrading.com. Read more articles by this author Writer's Bio: Lutz Muller is a Swiss who has lived on five continents. In the United States, he was the CEO for four manufacturing companies, including two in the toy industry. Since 2002, he has provided competitive intelligence on the toy and video game market to manufacturers and financial institutions coast-to-coast. He gets his information from his retailer panel, from big-box buyers and his many friends in the industry. If anything happens, he is usually the first to know. Read more on his website at www.klosterstrading.com. Read more articles by this author |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer Privacy Policy Career Opportunities

Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our Terms of Use.

© Copyright 2025 PlayZak®, a division of ToyDirectory.com®, Inc.